In London’s Victoria and Albert Museum is a small, silver sugar bowl from the late 1700s, complete with a tiny latch for a tiny lock. The mistress of the house would have kept the key herself, as sugar was far too precious to leave unprotected.

Today, sugar flows freely at every table. No longer spice or medicine, no more exotic or expensive than salt or pepper or clear tap water, sugar is now a basic and powerful commodity. It rarely concerns anyone who’s not worried about calories, insulin or childrens’ attention spans. With corn syrup currently wearing the black hat and ethanol a favorite of politicians, cane sugar has suddenly been rehabilitated. What sugar blues?

But Bill Haney and his documentary, The Price of Sugar (opening this weekend at the Opera Plaza Cinema) are here to show us exactly what it takes to bring us that stuff of sweetness.

I know, you’re already rolling your eyes or reaching for your mouse. Who wants to add sugar to the growing list of politicized food? Chocolate, coffee, corn, every fish and fowl and four-legged creature under the sun, and now this? Is nothing safe for the conscientious eater to enjoy?

If it makes you feel any better, know that centuries ago, cooks and diners were wrestling with these very same issues.

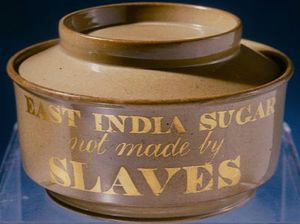

“EAST INDIA SUGAR not made by SLAVES”

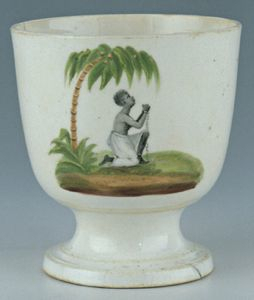

In 1791, abolitionists in the United Kingdom declared a boycott on sugar from the West Indies, where sugar plantations flourished with the help of the burgeoning slave economy. Diaries from the period mention how troublesome it was to entertain guests who were boycotting sugar, while Punch cartoonists poked fun at “anti-saccharrite” families that refused to offer sugar at teatime. There were valiant attempts to hold awareness-raising bake sales with cakes and cookies prepared without sugar or else only with sugar from India. (Thanksgiving cooks everywhere can empathize–how to fit the tofu next to the turkey?)

An ambitious little pamphlet, “Address to the People of Great Britain on the Utility of Refraining from the Use of West Indian Sugar and Rum,” written by Thomas Clarkson, set a publishing record for the time: 50,000 copies were distributed in the UK in only four months.

On the back of this anti-slave sugar bowl: “East India Sugar not made By Slaves. By Six families using East India, instead of West India Sugar, one Slave less is required.”

The slave-free sugar movement faced much greater opposition in the US, where rum was filling the new nation’s coffers. While Clarkson and his followers helped turn the tide against slave labor in the UK (an estimated 300,000 British families boycotted West Indies sugar) American abolitionists had another century of fighting before slavery was outlawed in the US.

But here’s the problem: Slave labor is not a thing of the past.

Ships no longer ply the Middle Passage, but we still have human trafficking in containers and vans. If trapping entire families on plantation land to work their whole lives, guarding them with rifles day and night, stringing barbed wire over their ceilings so they can’t escape, paying with vouchers for the company store or not bothering to pay at all, and enjoying the full support of governments do not all add up to institutional bondage — or slavery — then someone needs to rewrite the dictionaries.

In the US, the major sugar-cane states are Florida, Louisiana and Texas. A long-growing crop with intensive irrigation requirements, heavy chemical inputs and back-breaking, hand-maiming occupational risks, sugar cane is not an easy crop to grow. Increasingly, American growers depend on a mechanized harvest (especially after a lawsuit was filed in the mid-1990s demanding that companies pay their guest workers the contracted $5.70 a ton rather than merely $3.70 a ton.)

However, environmental devastation is still a serious issue. As sugar cane is re-framed by politicians and growers as an eco-friendly source of energy here in California, we need to keep a closer watch on the discussion. Close ties to Washington help big sugar companies maintain generous subsidies, while import restrictions keep domestic sugar cane prices artificially high.

So yes, there’s still a long way to go. Luckily for us, courageous and determined individuals continue to lead the way. Person by person, family by family, nation by nation…changes will happen.

THE PRICE OF SUGAR

Directed by Bill Haney

Landmark’s Opera Plaza

601 Van Ness Avenue

(415) 267-4893

The documentary really should be titled “The Life and Work of Father Christopher Hartley” since this Catholic priest, who compares himself to Mother Theresa, stars in the film. Father Hartley fought for years to improve the horrendous living and working conditions of undocumented Haitians on the sugar plantations of the Vincini family, powerful players in the Dominican Republic. The family has tried blocking the release of the film, and both the crusading priest and the director have received death threats. The film depends more on slow motion and plaintive music than data or historical context to make its points. In the end, though, I came away with an understanding of the human side — both the good and the bad — of this complex issue.

SMALL STEPS TO GOOD SUGAR

There are no easy answers. The US produces 80% of the sugar it consumes, so international free-trade sugar, already a small fraction of the industry, is just one part of the solution. Domestic sugar’s impact on ecosystems, energy production, public health and political power are other important considerations.

- Awareness and education are the first steps. Seeing the above documentary is one way to begin. There are many resources on the internet for anyone curious and committed. I’ve included a few links at the end of this post for those who’d like to read more. Taking on all the issues is overwhelming. Instead, choose subjects already close to you and learn how they relate specifically to sugar production and consumption.

- Spend your money wisely to express your desire for a better world. Do what you can when you can. Buying fair-trade sugar supports companies and cooperatives that meet international standards for worker rights and environmental sustainability. Go for little but consistent changes for the long haul. Our small individual acts really do add up.

- Spread the word. While you might not have a sugar bowl that speaks for you, there are many opportunities to influence others, whether it’s the office manager who stocks your company’s break room or the grocery store in your neighborhood or the bakery that’s going to craft your wedding cake. Ask if fair-trade sugar is an option, and if it’s not, ask why not.

- Finally, one of the most important things we can do is to write our elected representatives a letter to remind them that we want an agricultural industry in California that is environmentally sustainable and fair to its workers. The California Coalition for Food and Justice offers several different sample letters as well as a detailed tip sheet on how to meet your respresentatives in person. Join the coalition or sign up for their newsletter to keep in touch with food policy issues in California. You can adapt their language to your own specific concerns. Encourage your friends and family to write letters, too.

![]()

Look for these marks of fair trade certification on sugar that you buy.

SUGAR LINKS

If you’re interested in learning about the sugar cane industry, especially a little closer to home, here are some online resources:

- Sugar Knowledge International offers a basic description of how cane sugar is processed.

- Fair Trade Certified provides a fact sheet on fair-trade sugar.

- Read about the call for growing sugar cane in California’s Imperial Valley to provide energy and ethanol.

- Environmental Entrepreneurs estimates how many megawatt-hours of electricity might be converted from cane sugar fiber in California.

- The Center for Responsible Politics describes the electoral politics of sweeteners in “Iron Triangle of Beet Sugar, Cane Sugar and Corn Syrup.”

- For a historical view of Big Sugar from, of all places, The American Conservative, this critique of guest worker programs for the US sugar industry describes how growers take advantage of their workers.

- In its National Wetlands Newsletter, the Environmental Law Institute discusses how growing sugar cane in the Florida Everglades affects the ecosystem and taxpayers.

- Alter Eco, based in San Francisco’s Mission Bay, distributes fair-trade sugar. Their controversial financial model, melding the business structure of a corporation with the social mission of a nonprofit, helps them pursue their goal of mainstreaming free-trade products into supermarket chains.

Hey, thanks so much for this post! I’ve been trying to read Sidney Mintz’ Sweetness and Power, all about the history and politics of sugar, for almost a year now, but it’s great to have a shorter and sweeter (ha, ha) version of the story in convenient online form. (Oh, and I found you via Ethicurean’s Digest, in case you like knowing that kind of thing.)

Oh, and I for one am very interested in learning more about beet sugar in the States. My family is Dutch, and according to popular history beet sugar was invented or maybe popularized in the Netherlands for antislavery reasons like the ones you mention in your awesome post. Beet sugar syrup (sort of the beet equivalent of molasses) is one of my favorite sweeteners of all time, and I’ve never seen it in the States, so I’m curious to learn more about U.S. beet sugar production, if only for the off chance that someone will mention stroop…. (Oh, and please feel free to combine this into my earlier comment, of course.)

Hi,

I am researcher based in India and am presently working on a book for the Madras Chamber of Commerce & Industry which is a not-for-profit body that is 175 years old. The organisation was involved in the distribution of the sugar cups with the slogan “Not made by slaves”. I request you to please let me have a copy of the two photographs depicting the anti slave campaign. If there is a cost to these, please do let me know by email.

Regards