Along with 4 million other people in Washington, I’m trying to figure out how to keep warm and dry while waiting (and waiting…) to witness history in the making. Fuzzy boots and mittens with hand warmers and puffy rain pants are my own fashion statement for this inaugural ceremony. And while the 44th POTUS settles into his luncheon, enjoying “A Brace of American Birds” beneath a painting of Yosemite Valley, I’ll be making my way very very very slowly back up to Tenleytown…to a crock pot full of warming chili.

No, I’m not following Obama’s recipe. Our very own North Coast Journal up in Humboldt County got a hold of that one back while he was still campaigning. Truth be told, it’s a bit bland for me (thank goodness kitchen skills have nothing to do with diplomacy and fiscal policy), but since his presidency promises change and diversity, it seems fitting that his chili recipe calls for beans and tomatoes and green pepper, an unholy trinity for any Texan devotee of chile con carne. President Obama, even serves it on a bed of rice. If you’ve spent any time in the Lone Star State, then you know that all of those are verboten.

His predecessor’s recipe is still secret, though like other Red-State, Tex-Mex lovers, Dubya swears by Gebhardt’s chile powder, conveniently available in 3-ounce or 5-gallon containers. Serious chili cooks will, of course, make their own from dried chiles, toasted cumin seeds, Mexican oregano and garlic powder.

Here in California, at the more lucrative end of the wagon train routes, we became known for carne con chile, not chile con carne. Ana Begue de Packman, a descendant of the state’s first colonists and author of Early California Hospitality: The Cookery Customs of Spanish California (Arthur Clark Company, 1938) included a recipe for carne con chile with the note that “it is insisted by the Californians that the meat be given the place of honor.” Her version, while avoiding tomatoes and beans, included breadcrumbs for thickening and a handful of the local black olives.

Modern experts, such as Hal John Wimberly, the editor of the Goat Gap Gazette, a monthly that covers all things BBQ and chile, is astounded by West Coast cooks. “Californians put funny things into their chili. Green peppers. Celery. All kinds of garbage.” Don’t even get him started on the tofu or dried mushrooms.

The Mexicans have disowned the dish entirely. The 1959 edition of the Diccionario de Mejicanismos defines chili con carne as “detestable food passing itself off as Mexican, sold in the United States from Texas to New York.” Since cows arrived in Mexico with the conquistadors, we can safely assume that beef was not in the original recipe south of the border. Cornmeal and beans, however, are components of nourishing stews prepared by the original Americans. That some chili recipes include these ingredients, along with the ever-present chiles, seems only natural in a place where borders were frequently shifting.

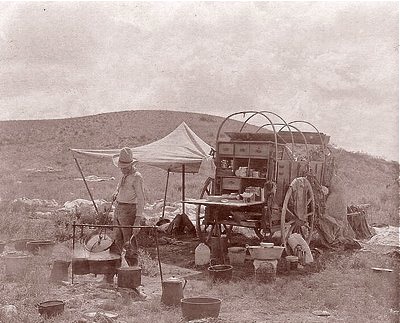

Chili stand in Haymarket Plaza, San Antonio, c. 1902. (From the Institute of Texan Cultures, UTSA)

Fortunately for my taste buds, purism has no place in my kitchen. I’m not averse to using ground meat instead of cubed, or — double sin! — shredding tofu skins to mimic ground meat. I’ve also been known to tilt a can or two of tomatoes and beans into my pot. And despite admonitions against overpowering the meat, I love doubling garlic and chiles, if not cumin and oregano. One of these days, I’ll brave a plate of five-way Cincinnati chili, with its layering of spaghetti noodles and oyster crackers. I’m one of those well meaning, curious cooks despised by Texans. If expanding flavor beyond the confines of a county jail counts as sacrilege, then, well, I always was comfortable with being a heathen.

Since the twisting paths of history are more interesting to me than any straight-laced doctrine, I’d like to point you to two recipes from the past. One comes from San Antonio, which has a good claim as the place of birth of chile con carne. The second recipe emerged from the kitchen of an early Californian.

In the 1800s, Mexican women set up chili stands at night in the main plazas of San Antonio, Texas. They become known and loved as the Chili Queens. The city’s commissioner, Frank Bushick, wrote in 1927 that the” chili stand and chili queens are peculiarities, or unique institutions, of the Alamo City. They started away back there when the Spanish army camped on the plaza. They were started to feed the soldiers. Every class of people in every station of life patronized them in the old days. Some were attracted by the novelty of it, some by the cheapness. A big plate of chili and beans, with a tortilla on the side, cost a dime. A Mexican bootblack and a silk-hatted tourist would line up and eat side by side, [each] unconscious or oblivious of the other.”

Mrs. Luce M. Trevino, 89, holds a 125-year old pot that she donated to the scrap metal pile during World War II. The pot was used by her mother for simmering chili in the first Mexican restaurant in San Antonio. (From the Institute of Texan Cultures, UTSA)

Original San Antonio Chili

This recipe comes from the Institute of Texan Cultures at the University of Texas San Antonio, where beans are barred from the chili pot.

2 pounds beef shoulder, cut into ½-inch cubes

1 pound pork shoulder, cut into ½-inch cubes

¼ cup suet

¼ cup pork fat

3 medium-sized onions, chopped

6 garlic cloves, minced

1 quart water

4 ancho chiles

1 serrano chile

6 dried red chiles

1 tablespoon cumin seeds, freshly ground

2 tablespoons Mexican oregano

Salt to taste

Place lightly floured beef and pork cubes in with suet and pork fat in heavy chili pot and cook quickly, stirring often. Add onions and garlic and cook until they are tender and limp. Add water to mixture and simmer slowly while preparing chiles. Remove stems and seeds from chiles and chop very finely. Grind chiles in molcajete and add oregano with salt to mixture. Simmer another 2 hours. Remove suet casing and skim off some fat. Never cook frijoles with chiles and meat. Serve as separate dish.

Carne con Chile Sepulveda

This recipe comes from Ana Begue de Packman’s historic cookbook, Early California Hospitality: The Cookery Customs of Spanish California. She offers a good tip for cooking with beef fat, essential for achieving the unctuous texture and rich flavor of the old versions of chili. As the name of the dish says, it’s about the meat. There’s no distraction of cumin or oregano even. If you side with Obama on the olive oil question, then be prepared for a thinner texture or else add a more breadcrumbs or dredge your meat in flour. And if you side with me on the point of tenderness, keep simmering the meat gently for a couple of hours. (Adapted by Mark Preston in California Mission Cookery.)

2 pounds beef chuck

1 teaspoon salt

1/4 teaspoon black pepper

2 tablespoons fat from the chuck

Sauce:

4 ounces dry red chiles

2 tablespoons fat from the chuck

2 tablespoons breadcrumbs, toasted

1 clove garlic, mashed in salt

1 tablespoon vinegar

1 cup black olives

Cut the meat in chunks, removing as much fat and gristle as possible. Brown a little of the fat to render it, to grease the skillet. Use no fat if the meat is fatty already. Add the chunks of beef and season with the salt and pepper. Brown it well and set aside.

Stem and seed the chilies. Wipe them clean. Put them in a stew kettle and pour boiling water over them. Cook until the skin easily separates from the chile meat. Rub the chile-meat through a sieve. This should make about 1 1/2 pints of red chile puree.

Heat enough of the fat to render 2 tablespoons in an iron skillet. Add the toasted breadcrumbs and the garlic, mashed in salt. Stir constantly until a light golden color. Pour in the chile puree, garlic and vinegar. Simmer 15 minutes. Add the meat. Cook 10 minutes longer. Serve, garnishing with ripe olives.